A Humber History,

Why is the Humber still a significant First Nations district and recognized in Canadian legislation.

Major source: Humber River, The Carrying Place published by TRCA (Toronto Region Conservation Authority) in 2009, and financed by the Canadian Heritage Rivers System , a multi jurisdictional body involving both the federal and Ontario governments, and whose charter states

“The Canadian Heritage Rivers System respects Aboriginal peoples, community, landowner and individual rights and interests in the nomination, designation and management of heritage rivers”

In 1999, the Governments of Canada and Ontario recognized the Humber River as a Canadian Heritage River, and 10 years later, the Toronto Region Conservation Authority published this celebratory book which gather historic references about the area, as well as lists the values a healthy Humber watershed contributes to the region. These values are at risk from the Crosstown extension.

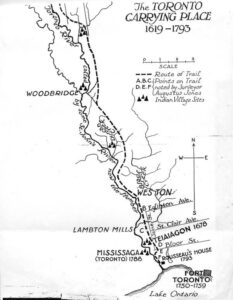

This document is a precis of the information in the TRCA book, plus information from other sources. The book includes the map below and has the bibliography to support the statements.

Archaeologists have discovered evidence of human occupation in the Humber watershed going back 12,000 years. Between 7000 BC and 1000 BC, seasonal settlements existed, and those settlement show the first evidence of trade with goods flowing between the Arctic and the Gulf of Mexico. Ontario Petroglyphs have been dated to this period.

About 1,000 BC agriculture is introduced with corn, beans and squash cultivated. Villages tend to be located on rivers and creeks where there are fish and fresh water.

Ontario’s first Governor, John Graves Simcoe travelled the Humber in 1793; his journey is recorded in his diary. Augustus Jones was the provincial surveyor and he was responsible for the first surveys of the area. The map below is based on his work, and clearly shows the extent of the Carrying Place Trail. Of particular note, the trail sometimes is adjacent to the watercourse, but for much of the trail, it is located on the table lands sometimes hundreds of meters from the river.

Ontario’s first Governor, John Graves Simcoe travelled the Humber in 1793; his journey is recorded in his diary. Augustus Jones was the provincial surveyor and he was responsible for the first surveys of the area. The map below is based on his work, and clearly shows the extent of the Carrying Place Trail. Of particular note, the trail sometimes is adjacent to the watercourse, but for much of the trail, it is located on the table lands sometimes hundreds of meters from the river.

In the Mount Dennis area, the trail goes around what is now Eglinton Flats, probably because the Flats are frequently flooded and boggy, while the table lands sit on sand and gravel and are usually dry and stable and thus more suitable for people carrying goods.

The published map shows the location of known First Nations villages, and of Simcoe’s campsites. This is clear evidence that the area surrounding Eglinton Flats, including the valley walls and table lands, were known to be of major significance to First Nations at the time of first settlement.

The Humber meets the definitions of a navigable waterway as defined by the Navigable Waters Act of 2017, and the Heritage Rivers System. Its use as a transportation corridor was documented by the first Governor of Ontario, (Upper Canada).

We believe this continued recognition by agencies of both the Federal and Provincial governments confirm that development in the Humber requires full consultation with the multiple First Nations that continue to use the area.

Carrying Place Trail was used by multiple First Nations, that shared use is the basis of the historical initiative by the Societe d’histoire de Toronto, and recognized as significant by City of Toronto and the National Trust.

As Project Manager alongside La Societe d’histoire de Toronto, Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation, Huron Wendat Nation, Six Nations Confederacy of the Grand, Heritage Toronto, the City of Toronto, Lambton Historical Society, the Swansea Historical Society, Susan Robertson managed the first major phase of implementation of the Parc Historique vision. Bringing the history of the Humber River to life, 13 story circles 52 interpretative signs and trailheads were installed in the Lower Humber Valley, connecting to the Waterfront Trail. Deemed the “greatest contribution to First Nations history ever made by the City of Toronto” by the former Chief, Carolyn King, it was National Trust of Canada Award Winner for Volunteer Contribution, in 2011.

Since the various historical agreements created what today would be considered an easement, acknowledged by all the regional First Nations and by New France, that easement could not be negotiated as part of the Williams Treaty, as the Treaty only dealt with the transfer of rights and value between the Crown and the Mississauga’s of the Credit. The rights to continued use and management of the Carrying Place Trail and Humber Valley is retained by the multiple First Nations of the Great Lakes basin.

The pre-colonial agreement was recorded in European history in 1701 with the signing of the Great Peace of Montreal which included an exchange of wampum belts and included the French settlers in New France. That agreement was based in part on the earlier Dish with One Spoon wampum belt agreement.

The following items give an insight into the recognition of these events in the history of Ontario.

Map: Published in 1933, authored by CW Jeffries ( eponymous CW Jeffries Collegiate on Black Creek at Finch) and based on initial surveys of Augustus Jones and diary of John Graves Simcoe.

In 1795, Augustus Jones surveyed York,. On December 24, 1795, Jones was directed by Lieutenant Governor John Graves Simcoe to survey and open a cart road from the newly planned settlement of York, Upper Canada to Lake Simcoe. Jones began the planning work the next day.[21] On the 29th of that December, Jones was given the assistance of thirty of the Queen’s Rangers for the road’s construction. The work began January 4, 1796, on this road, which would become Yonge Street. Jones worked as the effective master builder in addition to his title as surveyor. The road reached Holland Landing on February 16, 1796, and Jones returned to York on February 20 to inform the Lieutenant Governor that the road was completed.[22] This first incarnation of Yonge Street measured some 34 miles and 53 chains.[23] For the rest of 1796, Jones spent his time surveying Newark, Flamborough, Grimsby, Saltfleet, Beverley, York and Coot’s Paradise.[20]

Working as the Deputy Surveyor, Jones began to build good relations with the Mississauga Ojibwa Indians and Mohawk Indians of the area. He became fluent in the languages of these groups and earned the trust of many members of the tribes, including influential members like Joseph Brant, of whom he became a good friend.[3] In 1797 the head chief of the Mississaugas in the Credit River area Wabakinine, as well as his wife, were murdered by a member of the Queen’s Rangers. Wabakinine had been a very beloved chief and seen as a firm ally of the British. His murder shocked the members of his band and other local Ojibwa bands. Charles McEwan, the killer was charged and tried, but the Indian witnesses did not attend the trial and he was subsequently acquitted for lack of evidence. Nimquasim, a local Indian chief, met with Augustus Jones on February 15, 1797, and confessed to Jones that he and the local Indian bands were inclined to wage open war against the British over the event. Jones relayed this information to British administrator Peter Russell. The town of York had about 675 white settlers and 135 soldiers, a number that Russell believed might not be sufficient to address an Indian rebellion. If a winter rebellion transpired York would be cut off from large garrisons at the Bay of Quinte and the Niagara Peninsula. Russell and John Graves Simcoe both anticipated rebellion for the next year or so, but it never came. Joseph Brant, a Mohawk chief who had travelled to England cautioned the tribes against rebellion as he knew the military strength of the British was likely to render any war a losing one. Russell, however, set out to undermine alliances and friendships between the Indian bands of southern Ontario, fearing such an uprising.[24]

Jones spent 1797 surveying Pickering, Glanford, Oxford and Blenheim.[20] His survives duties in 1798 included Burford, Lake Shore Road, the Humber River, the Grand River, Uxbridge, Gwillumbury and the de Puisaye settlement.